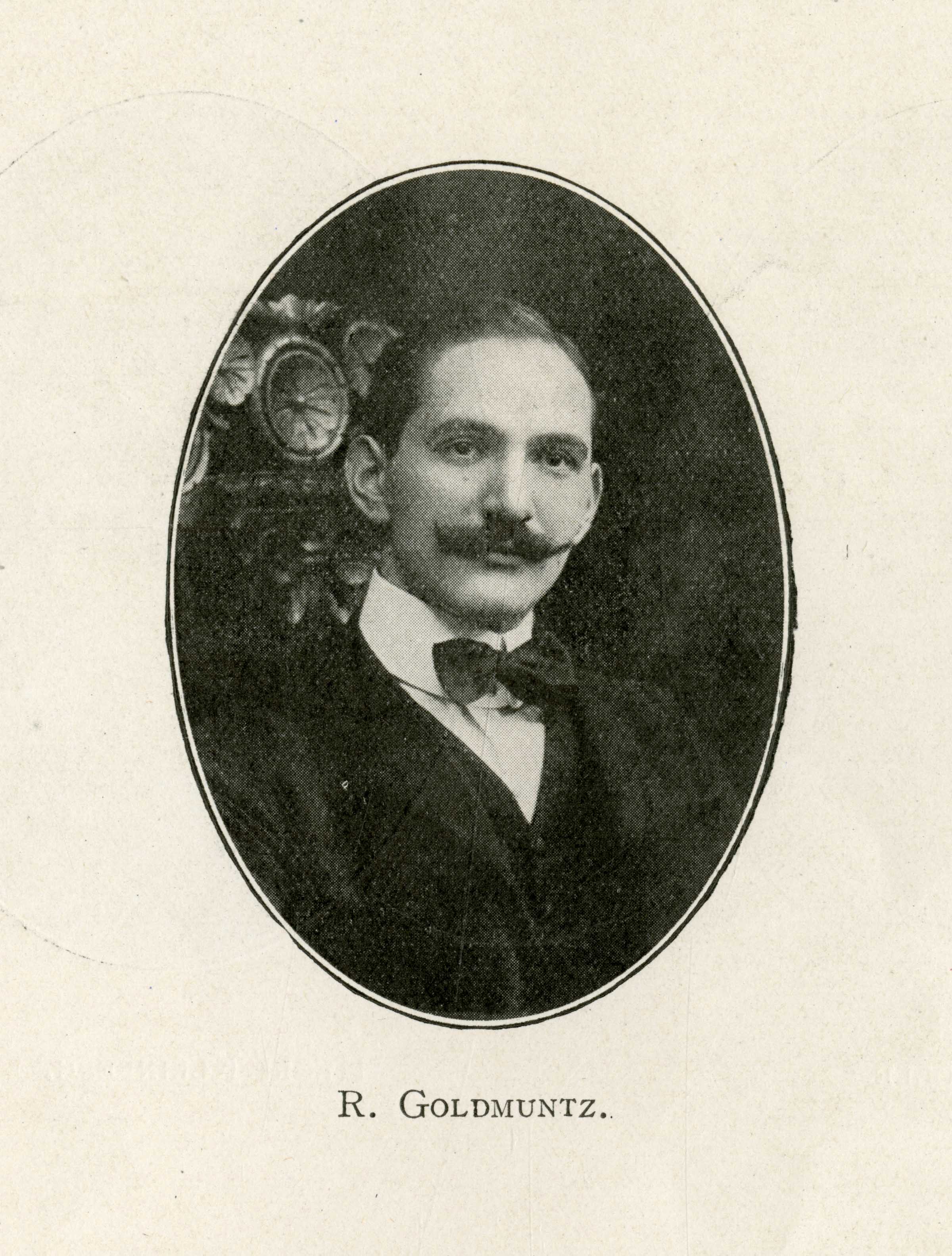

Romi Goldmuntz

05 June 2019 - 11:12

Romi Goldmuntz was born in Cracow (Galicia), then part of Austria, on 8 July 1882. He was one of eight children. When he was two, his parents moved the family to Antwerp.

At fifteen Romi, like many East-European Jews, became a diamond cutter and immediately joined the Antwerp Diamantbewerkersbond [General Diamond Workers’ Association of Belgium] (ADB). By 1904 he and his brother Leopold had become manufacturers. His business grew phenomenally, and by 1920 employed 600 workers.