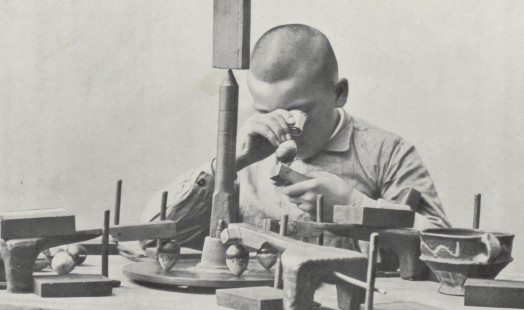

Specializations within ‘the Trade’

A rough diamond is dull and virtually always uneven in shape, requiring several processing steps for the stone to acquire the shine needed to be placed in a jewel. At first, ‘polishing’ comprised all processing procedures. Over the course of the eighteenth century, specializations emerged within the trade. Each processing stage became a separate trade at that point, each one with its own specialist skills and corresponding status.